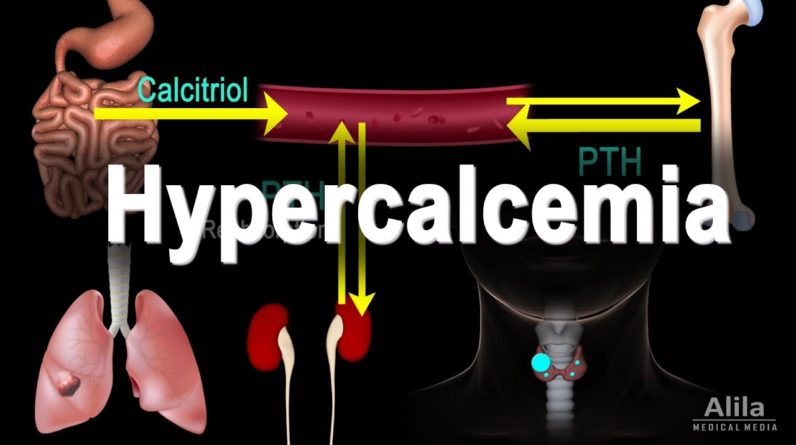

Hypercalcemia refers to abnormally

high levels of calcium in the blood. Dietary calcium enters the blood through the

small intestine and exits in urine via the kidneys. In the body, most calcium is located

in bones, only about 1% is in the blood and extracellular fluid. There is a continual exchange

of calcium between blood serum and bone tissue. The amount of calcium in circulation is mainly

regulated by 2 hormones: parathyroid hormone (PTH) and calcitriol.

PTH is produced in the parathyroid

gland while calcitriol is made in the kidney. When serum calcium level is low, PTH is upregulated.

PTH acts to promote calcium release from bones and reduce calcium loss from urine. At the same

time, it stimulates production of calcitriol, which promotes absorption of calcium in the small

intestine while also increases reabsorption in the kidney. Together, they bring up calcium levels

back to normal. The reverse happens when calcium level is high. This feedback loop keeps serum

calcium concentrations within the normal range. Hypercalcemia is generally defined as serum

calcium level greater than 2.6 mmol/L. Because the total serum calcium includes albumin-bound

and free-ionized calcium, of which only the latter is physiologically active, calcium levels

must be corrected to account for albumin changes. For example, increased albumin levels produce

higher serum calcium values but the amount of free calcium may still be normal. On the other

hand, in conditions with low blood pH, albumin binds less calcium; releasing more free calcium

while the total serum calcium may appear normal. Most symptoms of hypercalcemia can be

attributed to the effect it has on action potential generation in neurons.

High levels of

extracellular calcium inhibit sodium channels, which are essential for depolarization.

Hypercalcemia therefore reduces neuronal excitability, causing confusion, lethargy,

muscle weakness and constipation. In most cases, excess calcium in the blood is a direct result

of calcium release from bones as they break down, becoming weak and painful. As the kidneys

try to get rid of the extra calcium, more water is also removed, resulting in dehydration,

excessive thirst and kidney stones. Extremely high extracellular calcium may also affect cardiac

action potentials, causing arrhythmias.

Typical ECG findings include short QT interval, and

in severe cases, presence of Osborn waves. While hypercalcemia may result from a variety

of diseases and factors, hyperparathyroidism and cancers are responsible for about 90% of

cases, with the former being by far the most common cause. In hyperparathyroidism,

PTH is overproduced due to benign or malignant growths within the parathyroid gland.

An existing cancer elsewhere in the body can cause hypercalcemia in 2 major ways. First, some

cancer cells produce a protein similar to PTH, called PTHrP, which acts like PTH to increase

serum calcium. Unlike PTH, however, PTHrP is not subject to negative feedback; consequently,

calcium levels may keep rising unchecked. Second, cancers may spread to bone tissues,

causing bone resorption or osteolysis, and subsequent calcium release into the blood.

Hypercalcemia treatment consists of lowering blood calcium levels with a variety of drugs, and

addressing the underlying cause. While treatment outcome for hyperparathyroidism is generally

excellent, prognosis for malignancy-related hypercalcemia is poor, possibly because it

usually occurs in later stages of cancer..