Hi I'm Dr. Masha Livhits and this is Dr. Michael Yeh. We’re endocrine surgeons here at at UCLA and today we'll be talking about causes of high calcium. So please ask any questions you have on Twitter with #UCLAMDChat or comment below the video feed. So I thought we'd start just by talking a little bit about calcium and what it is and what it does. You're probably familiar with what calcium does in the natural world many living things many animals use calcium to build their skeletons. Here's some seashells. Here's a mastodon and any white sand beach you've ever walked on is made of the crushed up skeletons of marine organisms made of calcium.

It's also a key signaling agent in the body and that allows our heart to beat our central nervous system to work. Our muscles are all twitching and firing and moving all because of the movement of calcium–it's fascinating. Calcium moves in and out of cells, it moves within cells and the mere fact that I can move my hand and think and talk to you right now means that calcium is moving in my brain. I know you're not very impressed but we'll keep going. Calcium is a mineral and calcium is a salt. A mineral is like something like a rock, something solid and we see that not just in the seashells I showed you, but also in the human skeleton. When I say calcium is a salt, a tiny amount, less than 1% of the calcium in the human body is dissolved. Very much like you might dissolve some table salt in water. It flows around in our blood, it a dissolve within the cells of our body. And as I tell my kids: the human body is a very delicate, relies on a very delicate balance of water and salt.

So the salt form of calcium in our body is sort of divided half and a half into a bound form and a free or ionized form. The bound form is stuck to blood proteins and other complexes and the free form, the ionized calcium, is really free-floating in the blood.

We'll talk about that more when we get to the significance of high blood calcium levels. Calcium is tightly regulated. You've probably heard the term electrolytes. Electrolytes and salts means the same thing and the body has a very precise way of regulating the amount of sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium in our bloodstream. And the reason I have this photograph of these thermostats–an old style and a new style–is because the way calcium is regulated in the body is very much, almost identical, to the thermostat you use in your house. So if you set your thermostat to 72 degrees, if the temperature is below 72 degrees, the heater will be on and it'll warm up until it's 72 degrees and it will stop. In contrast, if somehow the temperature is above 72 degrees and the heater is still on, something's broken in your thermostat.

We'll come back to that a bit later. Where is the calci-stat or the thermostat for calcium in your body? Well it's located within 4 little known glands in the neck. They're called the parathyroid glands. It's different from the thyroid, ok? The thyroid and the parathyroids are neighbors, but they do separate things. These four little parathyroid glands are the sole regulators of blood calcium in your body. Something so important assigned to a very tiny organ.

What's weird is hardly anybody has heard about the parathyroid glands. Everybody knows you got one nose, two eyes, but nobody knows you've got four parathyroid glands. So that'll be the focus of some of our lecture today. This is how the parathyroid glands work. So they're up there, these tiny little things in your neck; each one is tiny–about the size of a grain of rice or a millet seed.

And the PTH, the job of parathyroid hormone or PTH, is to raise the blood calcium level. It's like the heater going on in your house, right? And like I told you before, that most of the calcium in the body is in the bones. So one way that PTH acts is by going to the bones and commanding a little bit of the calcium to come out. Did you want to elaborate on this? Other ways, is that it acts through vitamin D, a second messenger to increase our ability to absorb calcium from the gut. And the last thing that PTH does is, we tend to lose a little bit of calcium in the urine whenever we go pee.

So PTH goes to the kidney and tells the kidney to be better at saving calcium, bringing it back from the urine so it doesn't go out in the toilet bowl. These are the actions of PTH or parathyroid hormone. Ah, how are the PTH levels regulated by calcium? This is just an s-shaped curve showing how the thermostat works. And along here, if we move this way, as the the free calcium– remember free calcium is bound and free– so the thermostat responds to the ionized or free level. As we come up here, look at the PTH that's secreted. It suddenly goes down and the steep s-shaped curve means that as soon as calcium gets to the right level: boom. The secretion of PTH goes down, the heater shuts off, you've reached 72 degrees, you're nice and comfortable.

Let's imagine we move left on this curve.

That's the calcium going down, going down, going down, then all of a sudden, the PTH gets secreted by the parathyroid glands, again. So that's like the heater going back on. Very simple.

So just to emphasize that's in a normal person. This is the normal relationship between calcium and parathyroid hormone level and that the body uses to try to keep the calcium level normal. So we'll go over later on examples of when this curve is altered because there's a problem usually with the parathyroid glands. Great So let's talk about some causes of high calcium. We'll start with a general overview. So we talked about the different areas that where calcium is stored in the body, mostly in the bones, how it's excreted in the urine So why would the calcium level be high? It would be because there's more entry of calcium into the circulation compared to exit of calcium out of the body through either urine excretion or deposition into the bone. There are many ways that this can happen.

Either the bone has increased reabsorption or there's increased calcium intake–increased intake by the GI system for example– or decreased excretion of calcium by the kidneys. The causes are– really, the first thing that we always want to do when the calcium level is high is to repeat the level. There could always be one spurious lab result. Some dehydration could temporarily cause the calcium level to be high. There could be an issue with the lab. So one high calcium should always be repeated. And then as we discussed, a lot of the calcium in the body is bounded by protein, a protein called albumin. So we want to make sure that the actual free calcium in the body, the calcium that's available for use in the circulation, that that is high as well. So we want to know that the calcium corrected for albumin or protein, whether that is high or not. Most patients have a normal protein or albumin level so we can trust the total calcium level in the bloodstream.

The exceptions would be an athlete with a very very high protein diet. Those patients may have high albumin levels.Then people with kidney failure with severe malnutrition may have low protein or albumin levels. So in those cases, the ionized calcium which directly measures the free calcium circulating in the bloodstream might be more accurate. However, the ionized calcium may be less reliable in laboratory tests. Yeah, so it's a paradox, right? So the ionized calcium, once again, the free calcium, is a direct measurement of the free-floating calcium available in the blood. But we've noticed that, you know, each laboratory test has a little noise to it. And we notice, we measure the ionized calcium several times in the same patient, that seems to fluctuate a little bit more. So we prefer total calcium levels and the patient who has normal albumin that is blood protein levels. So then when we confirm that the calcium really is high there are two main forms: is it dependent on parathyroid hormone or is it independent of parathyroid hormone? Meaning is it a problem with the parathyroid gland, hyperparathyroidism that's causing high calcium.

Or is it independent of that? And in most patients, it is hyperparathyroidism. So that's that figure over here, the pie chart you can see most cases of high blood calcium levels are due to some form of hyperparathyroidism. The minority of people, it's not related to hyperparathyroidism. In those cases, it's more likely due to cancer or malignancy. We're not talking about parathyroid cancer, that is something that sometimes patients are concerned about. Could the parathyroid gland itself be a cancer? We're talking about other forms of cancer not from the parathyroid gland that may cause calcium to be high.

And I'll go into this a little bit more in a minute. Now hyperparathyroidism is the most common cause of high calcium, particularly in the outpatient setting and patients who are fairly healthy, otherwise. It is more common in women and up to one out of 400 women, particularly in their 50s and 60s, have hyperparathyroidism. It affects 1 in 1,200 men. So it's actually fairly common, particularly in women, but not that much is really known about it yet for a lot of people. The average age of diagnosis is about 50 to 55 and the prevalence has really increased. So you can see with the years kind of going from 1995 to 2010, we were discovering more and more cases of hyperparathyroidism. And there's probably a combination of reasons for that and one is just because of screening. In a regular metabolic panel, when we check electrolytes, calcium is in that panel. And so we're detecting more patients who have earlier, fairly asymptomatic disease potentially, who are detected because of a high calcium level. So let me give you a very typical example of a patient that we see in clinic on a very regular basis. A fifty-three year old woman who was having a routine and physical exam with her doctor and a high calcium was found on her labs.

When we go into her history, she does have a history of osteoporosis. She's not taking any vitamins, nutrients, or medications that could raise the calcium. And there's no family history that would suggest a hereditary form of high calcium. So when you go into our laboratory test you see that the calcium is 11.3. So that's above the upper limit of normal in our lab which goes up to 10.3 and that parathyroid hormone level is inappropriately elevated– it's over 100. Her kidney function is normal, that's the creatinine here, and her vitamin D level is also normal. So there's no reason why this parathyroid hormone level should be so high in the setting of high calcium. So that really points to hyperparathyroidism. Let's go to another case which would be the malignancy that I talked about. So the most common cancers that would cause high calcium would be breast cancer, kidney cancer, lung cancer, a blood cancer called multiple myeloma.

Again, not parathyroid cancer and these are often cancers that are already metastatic or have spread. And the reason that calcium would be high would be that these tumors can secrete what's called parathyroid hormone-related protein, which acts in a similar mechanism to PTH, you can raise the calcium, can have metastases directly to the bone, increase your absorption of calcium from the bone or can produce an activated form of vitamin D.

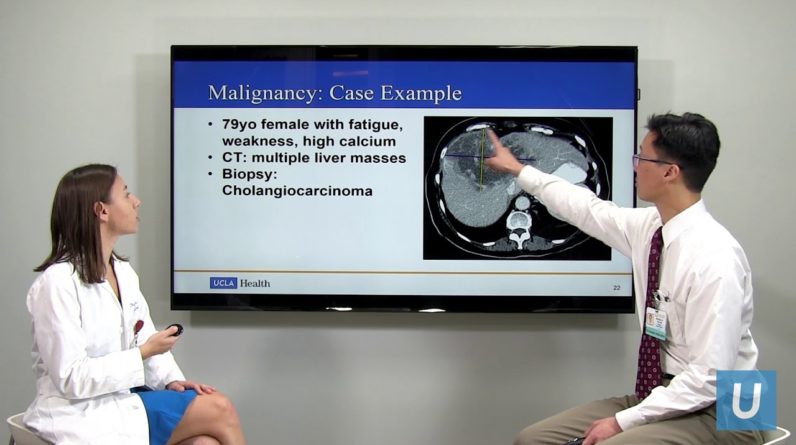

Usually, these cases are fairly evident, clinically. It's not subtle. The calcium is very high. So in hyperparathyroidism, most people have calcium's that are moderately elevated, maybe in the 11 range. But in cancer, the calcium is often above 13 and the parathyroid hormone level is very low. It's not normal. It's often in the single digits. And there's usually already clinical signs of advanced cancer, perhaps with metastases. So here's an example of that a 79 year old female who came to see us in clinic she really had not been doing well for several weeks with fatigue, weakness. She had gone to an outside emergency room and she was found to have very high calcium in the 13 range. But they did a number of imaging and workup and they couldn't find a reason for it, so she was referred to us for possible hyperparathyroidism as a cause of the high calcium level. When you look, clearly this is very concerning. The calcium is 13 but the parathyroid hormone level is 7. That's very low, that's an appropriate response from the parathyroid gland.

It's really telling us that something else is driving this calcium to be so high. Her kidney function is normal, vitamin D is normal, but this is that parathyroid hormone-related protein that I told you about. And that's pretty high. So we're worried about a cancer. And, indeed, when we got some more advanced imaging, we find– and this is a large mass here in the liver and she ultimately had a cholangiocarcinoma which is a bile duct cancer.

And so we were at least able to point her in the direction of the appropriate treatment. There are also medications that can raise the calcium level. This would include diuretics, or water pills, such as such as hydrochlorothiazide. Lithium, which some patients are on for bipolar disorder, can decrease the parathyroid sensitivity to calcium. There's a potential to take in a lot of calcium, for example, from tums that some people take for heartburn or excessive vitamin D intake. I would say that medications are– it's not very common for them to really cause a high calcium, would you agree? Yeah, most of these things are pretty rare and sometimes they'll just raise your calcium by a little bit. We don't see too much milk- alkali syndrome anymore because now you can go to the pharmacy, you can buy zantac or other types of antacids there. Vitamin intoxication is pretty rare, but the other night I was looking at this old Journal article saying that there have been incidents where people over fortified milk. Like, [inaudible] a little too much vitamin D and milk and, like, there was one area for one milk man that everybody vitamin intoxication.

Rare–but it has happened in history. Right, so just to a point that this is one of the medications: hydrochlorothiazide. This is a diuretic, or water pill, which is sometimes used to control high blood pressure and it decreases the calcium excretion through the urine. And it can be a cause of high calcium in the bloodstream because there's less calcium being excreted from the urine. So there is a study of 220 patients who had high calcium in the setting of hydrochlorothiazide use. And what they found was that when they stopped the medication in 83 patients, 59 still had high calcium. So ultimately 53 of the 221 patients were ultimately diagnosed with hyperparathyroidism. So that's about a quarter of patients where the initial thought was that the high calcium was due to hydrochlorothiazide, but really the medication just uncovered an undiagnosed primary hyperparathyroidism. But this is important, you know, in a situation where you think there may be a medication that's causing calcium to be high, to stop the medication, if that's possible, recheck the levels, and see if the calcium comes to normal or remains high.

Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia– tough one to say. Or FHH, which is easier. This is a very rare genetic disorder and caused by a defect in a calcium sensing receptor in the parathyroid glands and in the kidneys. That can cause chronic high calcium. Usually moderate hypercalcemia. Calcium is in the high 10, low11 range and it's chronic, meaning patients pretty much always have high calcium, for really, most of their lifespan. This is very rare. So I said that hyperparathyroidism affects 1 out of 400 women. But only 1 in 80,000 patients, so statistically, it is very rare. In most of these cases, the parathyroid hormone level is low, but it can normal, which can make it a little bit confusing whether the patient has hyperparathyroidism or this FHH genetic condition. And this is where the 24 urine calcium is particularly useful. People with FHH have a very low urine calcium. Low like less than 100 micrograms per 24 hours.

So if you get the urine test and the calcium is normal, this actually rules out this condition. It's only if it's very low that we wonder if this may be the cause of high calcium and this can be confirmed with a genetic test looking at the calcium sensing mutation. We see a few patients with this every year, even though it's very, very rare, but these patients are pretty much fine. Everybody in their family has a slightly high calcium level.

You look back in time that had high calcium levels ever since they Kids and they're perfectly normal. It's just their thermostat is set a little higher than everybody else,were kids and they're perfectly normal, it's just their thermostat is set a little higher than everybody else. Right? so it's important to try to identify these patients because they don't benefit from surgery. As far as we know they don't have any of the consequences of hyperparathyroidism, which they don't have. This doesn't contribute to osteoporosis or symptoms and so these patients should just be observed without any surgical intervention. Some other kind of rare causes of high calcium, severe hyperthyroidism, or thyrotoxicosis, granulomatous disorders, those are sort of inflammatory disorders that can affect the lungs. Such as sarcoid; that red arrow is pointing to an enlarged lymph node there, which could be biopsied to confirm this diagnosis. People who really can't move around a lot, maybe are wheelchair-bound; that can cause high calcium.

These are pretty rare causes. So let's focus now on hyperparathyroidism and how we can come to that diagnosis. So again we went over the parathyroid glands. There are four glands located here that are close to that butterfly shaped organ which is the thyroid. And to emphasize, the thyroid and parathyroid have very separate functions as Dr. Yeh mentioned, the thyroid sort of controls the metabolism and the parathyroid glands control the calcium level. Primary hyperparathyroidism, simply put, is when the parathyroid glands make too much hormone which increases the blood level of calcium. Classically we see a high calcium and a high parathyroid hormone level, and in those cases the diagnosis is fair be straightforward. We know there's really only one thing that can cause high calcium and high PTH level in the same setting, which is hyperparathyroidism. However, increasingly we see patients where it's a little bit harder to make the diagnosis. They’re non-classical. Either the calcium is normal or the parathyroid hormone level is normal, and those are the patients that we need to do a little more work up for the diagnosis.

So this is the curve that we looked at at the beginning. There is a normal relationship in the green line between parathyroid hormone and calcium. And the yellow box is where most people sit. Calcium is in the high 8, up to maybe the 10- point range or so. And the parathyroid hormone level is in the normal range as well. And in most people, if the calcium becomes really high, the parathyroid hormone level will drop appropriately.

If the calcium is on the low side, the parathyroid hormone level may rise a little bit because your body's trying to regulate itself. It's trying to bring the calcium back to normal. So let's start with the case of if the calcium is low. The orange box is hyperparathyroidism, where the parathyroid glands are producing more hormone. The yellow box, here, is normal parathyroid hormone levels and the gray box is hypoparathyroidism. So we won't focus much on the hypoparathyroid patients, where the PTH is low. That’s typically seen after some type of surgery. Right, so this–it's tricky hypo means not enough. Hyper, too much. So yeah, so let's focus on hyperparathyroidism. So in this case where the calcium is actually on the lower limit of normal or abnormally low and we see patients in the orange box, where that parathyroid hormone level is high, we call this secondary hyperparathyroidism. So the main problem is not in the parathyroid glands. The parathyroid glands are actually reacting appropriately; they are producing too much hormone because they're trying to bring the calcium back up to normal.

So there are a number of conditions that can cause this secondary hyperparathyroidism. I'll go into vitamin deficiency in a little bit more detail, kidney disease, urinary calcium leak. Gastric bypass can also cause this. Gastric bypass is a special case and some of you watching us today may have had one of these weight loss operations. Gastric bypass causes– makes it very difficult for people to maintain normal vitamin D levels. And it's weird, we have people come in with gastric bypass and even if we test the vitamin D levels, sometimes it's normal. But in between those tests it's probably dipping down and those people tend to have either a normal or slightly low calcium and the PTH level is high. But then those people, we we avoid making the diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism in those people. We usually don't think about parathyroid problem until the calcium is high in gastric bypass patients. Yes I correctly is going to be okay so let's talk about a couple of the common conditions that may cause secondary hyperparathyroidism. So vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D we get from the sunlight. There also certain foods that can give us vitamin D.

But you know, now we're all appropriately afraid of skin cancer melanoma and we're not in the Sun as much as we used to be. So it's very common for people to have vitamin D deficiency, even living here in Southern California, where there's a lot of sunlight. Still, many people have chronic vitamin D deficiency.That is a very common cause of secondary hyperparathyroidism. So in a person where the calcium is normal, we want to make sure that the vitamin D is not low because that may be the reason that the PTH level is elevated.

So in this case we want to make the vitamin D really normal, above 20 or even 30 to make sure that if the PTH level is high– is that due to vitamin D deficiency or is it due to an actual problem in the parathyroid gland where it's producing too much hormone inappropriately? And as you mentioned, you know, PTH can remain elevated for quite a while after vitamin D deficiency. So in the setting where the vitamin D may dip down, come back up, dip down again, the PTH can remain elevated for a few months after the vitamin D has been repleted. So in these patients, we really want to make the vitamin D level normal for some time, at least six to twelve weeks. And then we check the labs at that point. And rarely, you know, sometimes we actually can uncover cases of primary hyperparathyroidism. So if you supplement the vitamin D and all of a sudden the calcium becomes really high, then we've uncovered primary hyperparathyroidism. However if the PTH level comes back down to normal, we've confirmed that it was secondary hyperparathyroidism. Another common thing that will cause the PTH to be high will be chronic kidney disease.

So as you can see in the graph here, as the kidney function declines– that's the GFR level– so as the GFR level is coming down, there are more patients who have elevated PTH levels. Those are the blue bars. So the PTH level will be over, you know, close to 100 and almost all patients when the kidney function is very, very poor. And so in those cases, again, you know, the PTH is actually being appropriately increased because the body tried to regulate the calcium. In chronic kidney disease, the calcium tends to be on the low side. The body has a hard time making activated vitamin D and so the body appropriately makes a little more at parathyroid hormone to try to bring the calcium back into the normal range. And so in patients with kidney disease like this, we only consider that they have primary hyperparathyroidism again if the calcium becomes high.

And then when there's an overreaction, we think there's probably an abnormality in the parathyroid itself. Just a clarification of terms– so when we say primary hyperparathyroidism, it means there's something wrong with the parathyroids and some of those people need parathyroid surgery. Secondary hyperparathyroidism means that the parathyroids are really innocent. They're just doing their job and trying to compensate for other things that are going on in the body. Another way to think about this is kidney failure causes a certain type of vitamin D deficiency. And remember that vitamin D, when activated by PTH, is what allows us to get calcium from our food. Normally when we eat food, most of the calcium in our food just leaves in the stool– 90% So if you can't get calcium from your food because you don't have enough vitamin D, where else can you get it? There’s only one place left: skeleton, right? So the PTH in those cases go up goes up to help you unlock calcium from the bone reservoir.

Okay and then another thing that can cause hyperparathyroidism at secondary is urine calcium leak. So calcium is filtrated through the kidneys and renal tubular dysfunction of the kidney can cause a leakage of calcium or too much calcium is excreted through the urine this can cause recurrent kidney stones. And in these cases again the calcium is usually normal, but the parathyroid hormone level is elevated because the body's trying to compensate for excessive loss of calcium through the urine. These people will have a high 24 hour urine calcium but in the setting of a normal blood level of calcium.

So that's kind of the tip-off. And these people can be treated with hydrochlorothiazide, which is the diuretic or water pill that we talked about before, that will lower them out of calcium that's being excreted into the urine. And this often will normalize the parathyroid hormone and also decrease the risk of recurrent kidney stones. Okay so now let's go into the category of patients who have a normal calcium level. So again, in orange is hyperparathyroidism where the parathyroid hormone level is too high.

So patients in this orange box where the calcium is normal: high 8, maybe low 10 range. But the PTH level is elevated and, again, we're trying to differentiate. Some of those people will have primary hyperparathyroidism, an actual abnormality in the parathyroid gland, but some of them will have secondary hyperparathyroidism, where the PTH is elevated due to some other reason. So we really want to rule out the secondary causes that we talked about: vitamin D deficiency, kidney dysfunction. This entity of normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism, where the calcium is normal but the PTH level is high, was first recognized in 2009 and we are increasingly discovering these patients. So how do we discover them? Usually, we discover hyperparathyroidism because the calcium is high in the bloodstream.

So now, about 80% of people are discovered through a routine blood test. Calcium is thought to be high and upon further workup we uncover that there's hyperparathyroidism. But in these patient,s the calcium is normal, so how would we identify them in the first place? It's usually through workup of osteoporosis or low bone mineral density. So there's an endocrinologist who's seeing a patient with osteoporosis that's maybe more severe than would be expected and they're trying to figure out is there some underlying cause. They check the PTH level and it's high.

And that's how patients usually are discovered. And in these patients where the calcium is normal we need to differentiate between appropriate versus inappropriate increase in parathyroid hormone level; rule out secondary hyperparathyroidism. So patients with normal calcium in hyperparathyroidism, this is disproportionately discovered in symptomatic patients. There has to be a reason why we're checking a PTH level, so it's usually osteoporosis, sometimes recurrent kidney stones, in contrast with hypercalcemia patients, which you get are often asymptomatic. Now this is not to say that these patients don't have symptoms such as not feeling well, fatigued, you know those types of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

But they're not as often to have severe osteoporosis at the time of diagnosis.

We don't fully know the natural history. So what would happen if we observe patients with normal calcium with hyperthyroidism? Some of them will just remain very stable, the calcium will stay normal even if we watch for 5 or 10 years and don't do any surgical intervention. But about 15 to 20 percent. As far as we know, will progress to having actual high calcium levels.

Right. Right this is really an important topic. Dr. Livhits and I are seeing a lot of patients coming into our office and endocrinology offices with this problem. And to summarize what it means is the blood calcium level is normal and the PTH level is high and we've made sure that the patient doesn't have a kidney problem or a vitamin D deficiency, right? So then we have this isolated high PTH level and parathyroid hormone level and we’re wondering what to do with it.

I think right now, most of those people probably don't have severe health problems related to an isolated high PTH level. We're still learning more about this disease. If we look at the entire scientific literature about this disease, they're no more than 10 articles. But I think most these people are probably not in danger and probably most these people don't need any specific treatment or surgery. Yeah and the optimal management for these patients definitely still something that we are doing a lot of research along with other groups to try to figure that out. We don't want to do an operation that might be unnecessary; might not help a patient's bones. That's that's the main thing we're looking at, but it is something that we certainly consider. So in the last group of patients, are those that have high calcium and those tend to be the easiest to diagnose. So in the orange box are patients of high calcium, high PTH level, almost all those patients will have classic hyperparathyroidism.

The diagnosis is fairly easy to make and a lot of those patients will be good candidates for parathyroidectomy. Then the yellow box: those are patients where the calcium is high but the parathyroid hormone level is normal. And we consider this to be inappropriately normal. Again, the body is trying to regulate itself. So if the calcium is high, usually the PTH level will be very low because the body's trying to bring the calcium back down to normal. So if the parathyroid hormone level is inappropriately normal, we think these patients probably still have an abnormality in the parathyroid gland. We call this normohormonal hyperparathyroidism. That's also a hard word to say. So the people in the orange box here, right, it's very hot in the house and heaters on full-blast. Clearly, the systems broken. These people, it's hot in the house and the heter is still kind of on.

You know it should be off, right? And so these people have a problem with negative feedback. It's amazing, you know a large fraction of people with hyperparathyroidism are having all sorts of health problems because of it– bone loss, fractures– all into this category. And it's so frequent that physicians, other physicians, won't even notice this, right? Because they see the PTH level and it's technically within the normal range. But what I want the audience understand is that it's not appropriate for the context, right? If it's hot in the house and the heater is still going, even a little, something's broken. And so I would like to call attention to this, just for patients and physicians alike, to recognize this important entity of normohormonal hyperparathyroidism. It's a great point. So how low should the parathyroid hormone be in the setting of high calcium? That's really that kind of grey box.

You know, the parathyroid hormone should probably be in the single digits, you know maybe, 12, if the calcium really is high. An appropriate response, you know, if the calcium is high for some other reason, like cancer, would be that parathyroid hormone level of 7 that we saw in the previous patient. A parathyroid hormone in the 30s or 40s would probably be inappropriately normal. Those would be the normohormonal patients. It's kind of a bit of a summary here about what we've reviewed. Remember the box here for normal, a lot of people— oh, and by the way, from day to day, if you check your calcium and PTH level from day to day you're going to move around that box a little bit, right? Some days, calcium might be a little high and the PTH a little lower and otherwise there's a sort of seesaw effect.

These people out here with high PTH, and high calcium: a classic primary hyperparathyroidism. Some people here have cancers. Remember, like the lady with the liver cancer was making that weird PTHRP business. Those causing high calcium from a non-parathyroid reason. And people over here tend to have secondary hyperparathyroidism, when the parathyroid was responding normally to a stimulus, such as kidney failure. And there are small nerve people whose parathyroid glands don't really work at all, and sometimes that's because they've had thyroid cancer surgery or something like that. Something has harmed the parathyroid glands. So this is just a summary slide. So most cases of a high calcium are due to primary hyperparathyroidism cancers are usually associated with very low PTH levels and are fairly clinically obvious.

And they're also very rare. So really the main cause of high calcium tends to be hyperparathyroidism. Patients who have high calcium and high PTH are fairly easy to diagnose, but these variants of hyperparathyroidism can be a little bit more challenging– where the PTH level isn't appropriately normal or maybe the calcium is normal with a high PTH. Those require a little bit more thorough diagnostic workup. Sometimes having a couple of repeat sets of labs really establishes the true diagnosis and pattern because what we're looking fo is that an appropriate relationship, as you mentioned, between the calcium and PTH level. Oh, here's some take-home points if your calcium–if you are found to have a high blood calcium level, maybe in a routine laboratory tests, you should check it again.

And Dr. Livhits talked about this earlier, but the way to think about this is: let's say you're driving your car around you feel you hear a funny noise from the back. You're not going to immediately take it into the shop. You're gonna listen for it again tomorrow. And and that's what we should do with our bodies, you know, we should use common sense and make sure the calcium stays high. Now, if it's high a second time then there's a 90% chance you could have primary hyperparathyroidism. That's just most common thing, right? And so it's amazing. This This this problem of calcium levels that are chronically high; high all the time. We had some data recently that showed it's happening to like 5,000 patients a year just within UCLA health. okay. We cover, we take everybody. You know, 1 to 2 million patients, right? So how often is this happening in the United States? A million times. Alright. And remember if your calcium is high and high more than once, you really have to look at that parathyroid hormone level. And that really should be checked on everybody whose calcium is persistently high.

Yep, and what we found is that even in our health system, not all patients will have that PTH level checked. So this is something where people can advocate for their own health, if you've had a couple of high calcium levels, really, that PTH level should be checked. It's true, you know, we doctors in the information age, we're flooded with results. On any given day, we've got 5000 lab results in our inbox. So you know on the other hand, you, as the patient, you only have one patient to look at: you. So if you notice that your calcium levels are high, might want to sit doctor and say, hey, you know what's the reason behind this? I think that's just being an intelligent patient. Yep, I agree. And then this is a set of, sort of a laboratory workup that we would recommend.

The calcium is high a couple of times, check the parathyroid hormone level. The serum calcium that we talked about, we want to see what the albumin is. That's the protein level. As long as that's normal then the serum calcium is pretty much, you know, what we tend to go by. Kidney function is creatinine, vitamin D level, phosphate.

Consider 24-hour urine calcium for, kind of, cases where we're still trying to make the diagnosis. And this is the most important laboratory tests and making the diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism. And many cases of primary hyperparathyroidism do remain undiagnosed, particularly where the PTH level might be inappropriately normal, for example. We worry a little bit about these undiagnosed cases. And maybe that's one of our most important messages to you today because we do meet people with undiagnosed primary hyperparathyroidism who are having bone loss and kidney stones, unnecessarily. Those people could just have a straightforward operation be cured of those problems. And so we're trying to unearth some more of these cases that remain hidden. Absolutely. So thank you so much for being with us today on our webinar: Causes of High Calcium. And we're happy to take your questions over Twitter. I think we've got a couple coming in. All right. So do you want to start with this top? one is: I am 67 years old and my calcium is 10.1. So normal in most labs go up to about 10.3. Sometimes 10.4. This is a patient with a calcium of 10.1, kind of in the upper limit of normal.

I heard that any level above 10 is abnormal, particularly at my age. Is that true? This is a question we get a lot is any calcium in the 10s abnormal? I would say not necessarily. You know each lab has its own reference range. I think when we start to get calciums of 10.3, 10.4, 10.5, then we really have to think about rechecking the calcium. And this person should probably at least have another check in a couple weeks and see where it goes. We've also been getting a lot of questions about, oh, is this calcium normal for my age? We're not really sure where that comes from because as far as we know, the scientific literature would suggest that calcium levels, or the normal range is the same for everyone, whether or not you're an infant or you're you're 90.

So you know we are cognizant that a lot of myths and fake news, unfortunately, can be spread on the Internet. So if you are looking, you know, if you want to, if you have a high blood calcium level and you want to investigate it and do some internet research, we encourage that, but make sure you go to reputable sources. So in this case I would encourage this lady to check it again in a couple weeks. I think that's great but that does lead us to the next question: is there an app that can determine whether I have hyperthyroidism? So there have been several algorithms, there's an app out there to try to establish. If you just plug in your numbers, calcium, PTH levels, whether that will tell you if you have hyperparathyroidism. None of these algorithms or apps are 100%. What we really look for is the inappropriate relationship between calcium and PTH and there can be a lot of gray, kind of, variation, changes over time.

So there's really no replacement for reviewing all your laboratory results with an experienced clinician in hyperparathyroidism who can look at your specific values and tell you if they really think that you have a hyperparathyroidism. Yes, so some of the cases, in some cases, establishing the diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism is easy. You see the calcium's high several times. The PTH is high several times and you have the diagnosis. I did meet some patients who, excuse me, who showed me this app on their iPad and it said oh you know plug in your values and the app will tell you whether or not you have primary hyperparathyroidism. I had a little fun with one of them. I deliberately put in– I hijacked their iPad–and I deliberately put in values that did not, that I knew were not compatible with primary hyperparathyroidism and the app said I had hyperparathyroidism anyway. So when I tried that I kind of lost a little bit of faith in some of these apps.

I mean, people have applied tried to apply machine learning to see whether or not there's a relationship or do we multiply the two factors of calcium and PTH, do we come up with an index? I mean these things are great, but but still we rely upon expert clinical judgment. So if you have questions about this, just go talk to your doctor. You're gonna have a lot better results doing that than, a lot of time, on the Internet. Alright, thank you so much everybody! Have a great day! Thanks